Intermittent fasting has gained significant attention as a popular strategy for weight loss.

However, its potential benefits extend beyond weight management.

This diet may play a role in reducing the risk of various chronic lifestyle diseases.

In this email, we will explore the essential aspects of intermittent fasting, helping you understand its merits and whether it lives up to the hype.

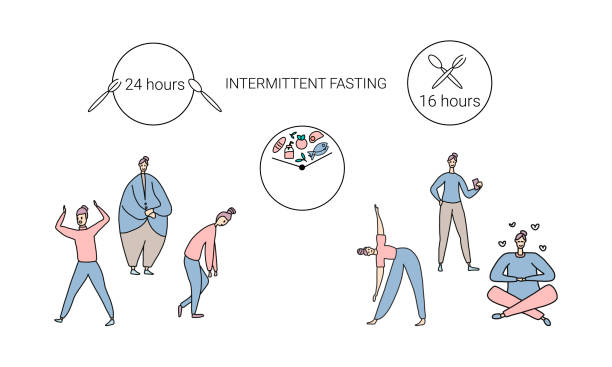

Intermittent fasting refers to a range of eating patterns that involve alternating periods of fasting and eating.

Fasting can last anywhere from twelve hours each day to several consecutive days.

These fasting patterns recur consistently throughout the week.

Among the most recognized forms of intermittent fasting are modified fasting, alternate-day fasting, and time-restricted eating.

Modified fasting, known as the 5:2 diet, consists of fasting for two non-consecutive days of the week while eating normally on the other five days.

Alternate-day fasting alternates fasting days with regular eating days without restrictions.

Time-restricted eating is particularly popular, limiting the daily eating window to four to twelve hours.

This induces a fasting period of twelve to twenty hours.

During the eating windows, individuals can consume food until satisfied without calorie restrictions.

The 16:8 pattern is a frequently recommended time-restricted eating method, allowing for eight hours of eating followed by sixteen hours of fasting.

Research on intermittent fasting often examines its effects on the body’s circadian rhythm.

The circadian rhythm, also referred to as the circadian clock, governs a twenty-four-hour metabolic cycle.

This cycle encompasses various bodily functions such as sleep-wake patterns, blood pressure regulation, mood balance, and hormonal activity.

Light and darkness, eating habits, and meal timing significantly influence this rhythm.

Emerging research suggests that extended eating periods of twelve to fifteen hours may disrupt the circadian rhythm.

Such disruption can elevate the risk of chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes.

A primary goal of intermittent fasting, particularly time-restricted eating, is to shorten the duration of daily eating.

This is achieved by extending the overnight fasting period.

The scientific investigation of the link between circadian rhythms and meal timing is referred to as chrono-nutrition.

Numerous benefits of intermittent fasting are attributed to fasting periods of at least twelve hours, with some studies suggesting that sixteen hours may be optimal.

Research indicates that during a fasting period of twelve to thirty-six hours, liver glycogen stores become depleted.

This leads to alterations in metabolic processes, yielding positive health effects.

Improvement in cholesterol levels is one notable benefit supported by both animal and human studies.

Intermittent fasting has shown potential in lowering total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol while increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

High levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides are associated with heart disease risk.

Additionally, intermittent fasting can enhance blood sugar control by reducing insulin resistance and increasing insulin sensitivity.

This results in lower fasting blood sugar levels and glycated hemoglobin, often referred to as HbA1c.

Research involving adult males with type 2 diabetes indicates that intermittent fasting may serve as a therapeutic approach, possibly reducing the necessity for insulin therapy.

Changes in body composition are another well-studied effect of intermittent fasting.

Several studies have documented weight loss of three to seven percent within eight weeks through intermittent fasting.

Furthermore, this method may promote fat loss.

Fasting using a fourteen-hour fasting window and ten-hour eating window has demonstrated effects on metabolic syndrome risk factors.

These include reductions in waist circumference, body fat percentage, and visceral fat.

Consequently, intermittent fasting may alleviate metabolic syndrome, a condition characterized by risk factors that heighten the likelihood of heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

In addition to these benefits, intermittent fasting has been linked to other health improvements.

A review involving over two thousand six hundred adult women suggested that evening calorie restriction and longer overnight fasting may decrease inflammation and lower the risk of breast cancer and other inflammatory conditions.

Observational research involving over twenty-six thousand adult men over a sixteen-year span suggested that reducing late-night eating could significantly diminish heart disease risk.

Areas of health that are currently being researched in relation to intermittent fasting include longevity and neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease.

Despite its numerous benefits, intermittent fasting is not without its downsides.

Some individuals may experience negative side effects, including increased hunger, irritability, mood disturbances, and difficulty concentrating.

Moreover, concerns about overeating during eating windows and feelings of being out of control around food may arise.

Quality of evidence is another consideration, as most research on intermittent fasting is based on animal studies.

Only a limited amount of long-term human research is available.

A review conducted in 2021 indicated that merely six out of one hundred four claimed health benefits of intermittent fasting were supported by moderate to high-quality evidence.

Thus, more rigorous human studies on the long-term health benefits of intermittent fasting are necessary.

It is important to note that intermittent fasting is not the only dietary approach that can yield similar benefits.

Calorie restriction, which involves reducing daily energy intake by approximately twenty-five percent without altering meal times, has shown positive effects on overall health.

Research suggests that the health outcomes associated with intermittent fasting may not exceed those of calorie-restriction diets.

Both methods yield comparable results regarding weight loss, body fat percentage, and metabolic risk factors.

However, intermittent fasting appears to offer greater adherence over extended periods compared to calorie restriction, suggesting it may be a more sustainable option.

The Mediterranean diet, based on the traditional eating patterns of the Mediterranean region, is another dietary approach that promotes health.

Like intermittent fasting, long-term adherence to the Mediterranean diet has been linked to a reduced risk of heart attack and stroke.

Research indicates that similar protective effects can be achieved through the Mediterranean diet without the need for fasting.

In conclusion, intermittent fasting encompasses various eating patterns characterized by alternating fasting and eating periods.

Time-restricted eating is the most popular form, utilizing principles of chrono-nutrition to lengthen overnight fasting and potentially decrease the risk of chronic diseases.

This approach may enhance cholesterol levels, blood sugar control, weight loss, inflammation reduction, longevity, and support for neurodegenerative conditions.

However, much of the existing research is based on animal studies, and further rigorous human research is necessary.

Alternative diets, such as calorie restriction and the Mediterranean diet, can also provide similar benefits to those observed with intermittent fasting.